Sermon preached by Rev. Dan Harper at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto, California, at the 9:30 and 11:00 a.m. services. The sermon text below is a reading text; the actual sermon contained improvisation and extemporaneous remarks. Sermon copyright (c) 2018 Daniel Harper.

N.B.: In 2022, I gave a talk on this same topic for an adult education class at the UU Church of Palo Alto. That talk was based on additional archival research, and in some cases I altered by conclusions on some minor points.

Sermon: This Congregation and Its Ministers, 1947-2000

On the surface, this is simply a sermon full of little stories about interesting people. But I also hope to make a serious theological point: in the words of Unitarian theologian Bernard Loomer: “We are born or created … as members of a Web of interconnections.”

To begin this history, you have to understand that we Unitarian Universalists see the relationship between clergy and congregation a bit differently than other religions. Unitarian Universalist congregations don’t have to have a minister. If a Unitarian Universalist congregation does decide to have a minister, it is the congregation that chooses which minister, and the congregation has the power to sever its relationship with the minister. With that in mind, let’s take a look at the relationship between our congregations and its ministers from 1947 to 2000.

Our congregation began in 1947 when Rev. Delos O’Brian, the regional representative of the American Unitarian Association, met with some Unitarians who lived in and around Palo Alto. He then placed advertisements announcing the formation of a Unitarian group. O’Brian called the first meeting on Sunday, April 6, 1947; and the following week, April 13, 27 people signed a charter membership roll. By April 27, 1947, the Palo Alto Unitarians had arranged with Nat Lauriat, then minister of the San Jose Unitarian church, to lead weekly worship services for them.

This group, calling itself the Palo Alto Unitarian Society, continued in this way some months, content to remain small, with fewer than 50 members. Nat Lauriat recalled a meeting in October, 1947, where “the general feeling was to proceed with great caution, and just have a pleasant little group.” Lauriat wanted to shake them out of that attitude, and he was pleased when the excessive caution at that October meeting “produced a reaction among the younger members for more action and growth.” Lauriat’s encouragement of action and growth soon paid off. Sixty people attended the first anniversary dinner, April 16, 1948, and voted to form a new congregation, the Palo Alto Unitarian Society.

By late 1948, the congregation learned about the new “Minister-at-Large” program offered by the American Unitarian Association (AUA). One minister-at-large was Rev. Lon Ray Call, who traveled from place to place across the country, spending two or three months at each place building excitement and enthusiasm, helping set up a congregational organization, and then leaving when he judged the new congregation would survive on its own.

Call arrived in Palo Alto on Easter Sunday, April 17, 1949. Within a month, membership had increased from 54 to 102. Years later, lay leader Bob Harrison recalled Call and his wife by saying, “Were they terrific!” With help from the Calls, the congregation saw there was strong demand for liberal religion in Palo Alto. The Calls also helped them see they would no longer be content to have Nat Lauriat come up once a week for an hour on Sunday; the congregation realized they would do best with a full-time minister. Based on Call’s recommendation, the AUA agreed to pay two thirds of the new minister’s salary.

In a historical footnote, some months after Lon Call left Palo Alto, the American Unitarian Association began a new policy, encouraging small congregations to form without professional leadership. These lay-led congregations, called “fellowships,” needed only ten members to formally affiliate with the AUA. If the fellowship concept had existed before the Palo Alto Unitarian Society organized, perhaps they would have been content to remain at 50 members in rented space. We owe our current congregation to Nat Lauriat’s encouragement, and Lon Call’s vision of rapid growth.

In mid-June, 1949, the Committee to Recommend a Permanent Minister voted unanimously to extend a call to Nat Lauriat. Lauriat turned them down, saying it wouldn’t be fair to the San Jose church. Next the congregation settled on Rev. Felix Danford Lion, then the minister in Dunkirk, New York. Lon Ray Call wrote to Lion on behalf of the congregation, encouraging Lion to accept the position without an in-person interview; Call added, “I do not wish to over-sell this church, but under the right leadership it can very quickly become one of our great [Unitarian] churches.”

In the years from 1949 to 1962, the Palo Alto Unitarian Church (they changed the name in 1951) did indeed become one of the “great churches.” Growth happened very quickly. By 1958, the congregation had grown enough to move out of rented space into its own building, built on a cabbage field at the intersection of Charleston Road and Adobe Creek. Growth peaked in 1962, when there were three Sunday services with six hundred children enrolled in the religious education program. Sunday school classes were held in 13 classrooms, the Fireside Room (which was built as a children’s chapel), and living rooms in houses of people who lived nearby. In order to remain at their preferred size of about 500 members, the Palo Alto Unitarian Church spun off several smaller congregations, including both the Sunnyvale and the Redwood City Fellowships.

The theology of both Lion and most of the congregation might be called vaguely theistic but strongly pragmatic, focused on social issues in the here-and-now. Rites of passage were very important, and Dan Lion officiated at scores of memorial services, child dedications, and weddings. (A historical footnote: If you know something about the 1960s folk music scene, you’ll be interested to know that Lion officiated at the wedding of a young banjo player named Jerry Garcia, and at the wedding of Mimi Baez Fariña, Joan Baez’s younger sister.)

By the late 1960s, the post-war Baby Boom was over, at the same time that people began to drift away from institutions like churches. Unitarian Universalist congregations across the U.S. declined in membership, and Palo Alto was no exception. By 1965, Sunday school enrollment in our congregation had dropped from 600 to 500; by 1970, enrollment dropped still further to 200. To quote a popular song of that time, the times they were a-changing.

During the 1960s, the congregation hired two assistant ministers. Bud Repp served as assistant minister from June, 1961, to September, 1962, while Dan Lion was on sabbatical. Even 1962 was the peak attendance of the church, Repp’s “salary was minimal and was not raised at the May congregational meeting,” so he resigned.

In June, 1965, the congregation hired Mike Young as assistant minister; he was also a Campus Minister at Stanford, so he was not at our congregation full-time. He was expected to stay just two years. Instead he stayed for nearly four years, and during his last year he was “under pressure from the Board to find a church of his own.”

In April, 1970, the congregation hired Ron Garrison as a half time “Minister to Youth,” although he was not actually an ordained minister. In January, 1971, Garrison began working full-time as Minister for Youth and Community Education. He helped organize both Thacher Preschool, and “Lothlorien,” an alternative high school that occupied what are now Rooms A through D. By 1972, the congregation had two full-time ordained ministers, so they only funded Garrison’s position at half time; he then resigned.

In July, 1971, Ron Hargis was hired as a Minister of Religious Education. Hargis later recalled he “had arrived at the church in the midst of a real conflict of staff personalities and church people.” A year after Hargis’s arrival, Dan Lion resigned to become Associate Minister at Community Church in New York City.

Why did Lion resign? The Palo Alto Times reported: “There has been occasional in-house controversy at the church … but members of Palo Alto Unitarian’s Board of Trustees say it is no more than the usual amount and has not been the impetus for Lion’s departure…. [One] trustee, Mrs. Gail Hamaker, said that some criticism was directed at Lion along the lines that he was perhaps providing too much leadership in church affairs….” Other documents in the church archives imply that Lion was forced out. With Lion’s departure, Hargis found himself as the sole minister of a congregation in conflict.

Back in 2002, Darcey Laine, minister of religious education at our church from 2000 to 2008, interviewed a few people who remembered Ron Hargis. One person remarked on the “creative ferment” during his tenure, another remembered him as “free wheeling, kind, and gentle,” while someone else recalled that his wife would sometimes share the pulpit with him. But another person felt he “lacked some properties that a good minister should have.” In any case, the Baby Bust continued through the 1970s, so that by 1973, Sunday school enrollment dropped to about one hundred.

In December, 1972, the Board of Trustees hired Sid Peterman to be an interim minister following Dan Lion’s departure. This was a new and experimental concept at the time: after the departure of a long-time minister, a congregation would hire a specialized interim minister for a year, someone who specialized in what we now call change management. Peterman later said he began doing interim ministry in 1973, so Palo Alto was his first interim ministry.

When he was ending his interim ministry in late 1973, Peterman wrote eight single-spaced pages of detailed critical analysis of the Palo Alto Unitarian Church. In 2002, lay leader Georgia Schwaar gave a copy of this report to Darcey Laine. Georgia wrote: “Some of the comments [in the report] … are not of current pertinence but much of it is still, surprisingly, à propos.” I will quote one such comment that in my opinion still applies to our congregation in 2018:

“It seems to me [Peterman wrote] to be quite clear now that I have been here a year that most of the [internal] problems facing this congregation are due to a unique history. Starting in 1949 [sic] with a handful of people and no possessions and a budget which was almost fifty percent underwritten by the AUA, PAUC grew by 1970 to be one of the largest churches in the region…. All this was done under the strong and effective leadership of one minister who served the church all during this time…. Many of the administrative and personnel practices in 1972 were the same they had been for a much, much smaller church. The developing and inevitable pluralism of a larger Unitarian church in the late sixties and early seventies were not taken into consideration and the result was the enforcement of an artificial dualism which not only caused great individual strains and discomfort but made the operation of the church far more difficult than it should be…. I stress this analysis because to fail to see what really happened in the past dozen years leads up dead-end roads of personalities and recriminations, rather than providing fruitful ways of continuing the growth — [both] spiritual and physical….”

In 1973, while Peterman was still on staff, the congregation called Bill Jacobsen to be a co-minister with Ron Hargis. Since there were those who considered Dan Lion to have been an autocrat, I suspect for some people this co-ministry idea seemed like a way for two ministers to keep each other in check. However, the co-ministry idea wasn’t financially viable. Beginning with the 1973 oil crisis, the United States entered a severe economic downturn, and the congregation could not afford two ministers. In response to the economic downturn, in 1975 both Hargis and Jacobsen stated they would automatically “offer their resignations effective January 1, 1978,” if the finances of the congregation did not improve. The finances did not improve. Hargis kept his promise and tendered his resignation on schedule. Jacobsen changed his mind and stayed on as the sole minister.

Not long after arriving at the Palo Alto Unitarian Church, Jacobsen got divorced. There are persistent rumors that subsequently Jacobsen engaged in what is called “sexual misconduct,” that is, he allegedly had sex with women in the church, perhaps including teenaged girls. Whether or not these rumors are true, I do feel there’s a change in the relationship between the congregation and the ministers from the 1970s on. Documents from the 1950s and 1960s show a mutual respect between lay leaders and the senior minister. By 1990, the documents seem to show a different relationship between the congregation and its ministers, characterized by a lower level of trust and a tendency to carefully circumscribe the authority of the minister.

I find it difficult to characterize the relationship between Jacobsen and the congregation. Apparently, lay leaders took on most of the leadership of the congregation, leaving him to focus on sermons. He is remembered for his strong sermons, yet those who were not humanists like him sometimes felt left out.

During Jacobsen’s tenure, attendance dropped enough that the congregation went back to one service. Nationwide, Unitarian Universalism declined beginning in the mid-1960s, beginning to grow again in the 1980s; but here in Palo Alto, it appears that growth didn’t begin again until the mid-1990s.

A September, 1988, survey revealed a mixed response to Jacobsen; comments ranged from “I like [his] sermons” to “The church lacks leadership from our minister.” Other comments from this survey questioned lay leadership, such as this one: “many of the lay leaders are quite sexist in their attitudes.” In December, 1988, Jacobsen announced that he was looking for another ministry position. Finally, in August, 1990, Jacobsen said he’d retire. He then helped form the Humanist Community of Palo Alto, and became executive director there.

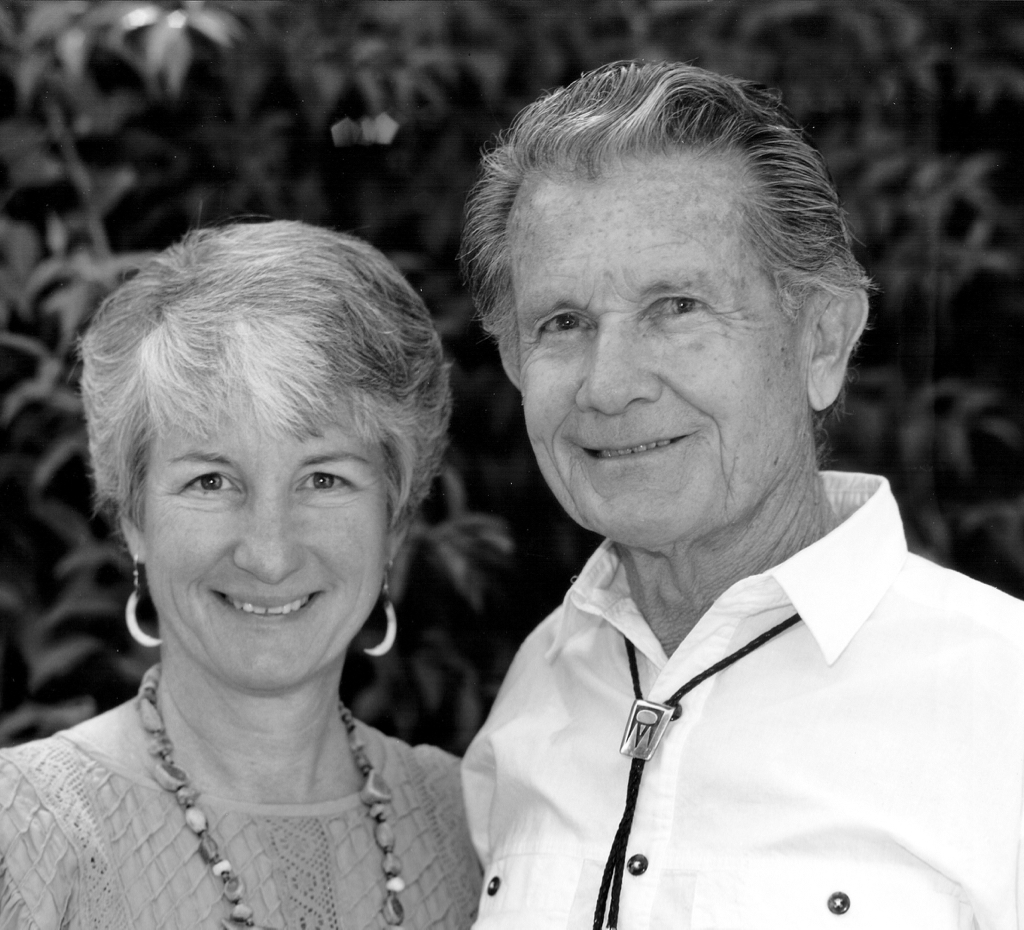

In 1990, our congregation hired Sam Wright as interim minister. Up to 1988, Wright had lived for two decades in the back country of Alaska with his first wife Billie. When she died, he wrote a book about his Alaska experience, which was published by the Sierra Club. Having read his book, I’d call Wright a mystic, in the naturalistic mode of Henry David Thoreau. One of the few mystics who had remained in the congregation during Jacobsen’s tenure told me they welcomed Wright’s arrival, and were deeply inspired by him.

Wright and his second wife, Donna Lee, considered themselves to be co-ministers (Lee was then in process to become a minister). Lee made a significant contribution to their interim ministry by writing a history of the early Unitarian Church of Palo Alto which existed from 1905 to 1934; Lee’s history remains important today because she had access to historical material that has since been lost.

During the one year that Wright and Lee served as interim ministers, the congregation added 69 new members.

After the interim ministry of Sam Wright and Donna Lee, the congregation called Ken Collier as sole minister in 1991. Later Collier said that he was warned away from taking the position as minister: “I was told [the congregation] was an aging, tired, isolated and somewhat troubled church that had enormous untapped potential. It needed to heal from its recent troubles….”

Two achievements stand out from the decade when Ken Collier was minister. First, Collier and a small group of lay leaders led the Welcoming Congregation program. This program, an initiative of the Unitarian Universalist Association, was designed to “undo homophobia” and ensure the congregation was a welcoming place for gay, lesbian, and bisexual persons. The congregation’s commitment to welcoming gay, lesbian, and bisexual people was soon tested. In 1993, Collier and his then-wife Marnie co-wrote a letter to the congregation in which they explained they were getting divorced, saying, “The central issue that we have not been able to resolve is that Marnie has come to realize that she is a lesbian-identified bisexual.” Marnie Collier and her new partner remained a part of the congregation.

The second major achievement during Ken Collier’s tenure was the introduction of the worship associate program, which continues today. Worship associates are lay people who share leadership with ordained ministers in planning and leading worship services. This is a distinct change from the 1950s and 1960s when Sunday morning worship was not a shared responsibility, but rather delegated to the minister.

By 1998, effective leadership by Ken Collier and lay leaders had helped congregation recover from its low ebb in the 1980s. To continue that growth, lay leaders decided it was time to start thinking about adding a second minister. In order to establish this second ministry position, the congregation hired Til Evans, an experienced minister of religious education and sometime faculty member of Starr King School for the Ministry, for a two-year interim ministry. Those who remember Evans speak of her with affection, and when a new garden was established next to the McFadden Patio, it was named the Til Evans Garden in her honor.

By 1999, the congregation had seen enough growth that members also voted to add another Sunday morning worship service. (Remember that there had been three services in the 1960s, but the congregation dropped to one service during the 1980s.) The task force charged with adding a second service included lay leaders Ruth Freeman, Cathy Leach-Phillips, and Ed Milner, along with the two ministers.

In August, 2000, our congregation called Darcey Laine to be the settled minister of religious education, and co-minister with Ken Collier. This was the first time since 1927 that there had been a regularly called and regularly ordained woman minister settled in the Unitarian congregation of Palo Alto. The previous one had been Rev. Leila Lasley Thompson, ordained and called in 1926 to the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto; she was the first woman minister called to any Palo Alto congregation, but resigned in 1927 when that old congregation could no longer afford to pay her (that congregation was defunct by 1934). I find myself astonished that, after having been such pioneers in women’s rights, it took Palo Alto Unitarians nearly three quarters of a century to call another woman minister.

Darcey Laine’s arrival provides a convenient ending point for this brief history. Before I end, let me tell you what struck me as I was researching this history.

I couldn’t help noticing that the relationship between congregation and ministers was never perfect, not ever. We human beings are fallible, which means we regularly make mistakes. Some said Dan Lion took on too much of the leadership of the congregation. Some said Bill Jacobsen took on too little leadership. You could, with equal validity, say that lay leaders during the 1950s and 1960s took on too little leadership, while lay leaders during the 1980s let themselves take on too much leadership. The relationship was never perfect.

We should never forget that human beings are fallible; this is a crucial theological point. Any time a human being thinks they are infallible, they become dangerous; the lone rangers who have no check on their own fallibility, they’re the ones we need to worry about (and there are numerous examples of the lone ranger phenomenon both in contemporary U.S. politics and among Silicon Valley executives). With that in mind, ideally our congregation will be a place where our relationships with others protect us from the worst effects of our own fallibility. This in turn suggests that fallible humans need share leadership with others, because this is the best way to help us through our mistakes and moments of fallibility.

To put this in theological language, what I’m saying is that we are part of a Web of interconnections. The dimensions of that Web are measured by trust, power, gratitude, forgiveness, transformation, and so on. And the balance of shared leadership is simply another way to measure the dimensions of the Web of interconnectedness that binds each of us together with all reality.

Notes

The primary source for this sermon was documents from the in the UUCPA archives, including those listed below. I also referred to my notes of a few reminiscences from long-time members, notes which remain confidential.

Published sources:

Loomer, Bernard. Unfoldings. Berkeley, Calif.: First Unitarian Church of Berkeley, 1985

Ross, Warren R. The Premise and the Promise: The Story of the Unitarian Universalist Association. Boston: Skinner House, 2001.

Ulbrich, Holley. The Fellowship Movement: A Growth Strategy and Its Legacy. Boston: Skinner House, 2008.

Wright, Sam. Koviashuvik: A Time and Place of Joy. Sierra Club Books, 1988. (Contains a brief reminiscence of Dan Lion.)

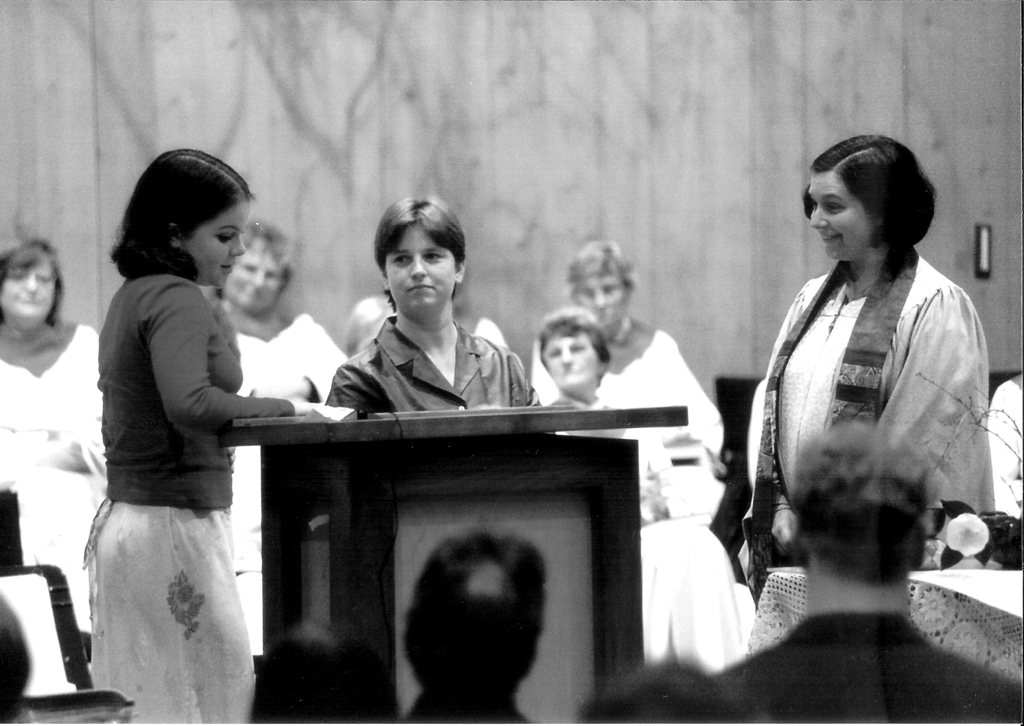

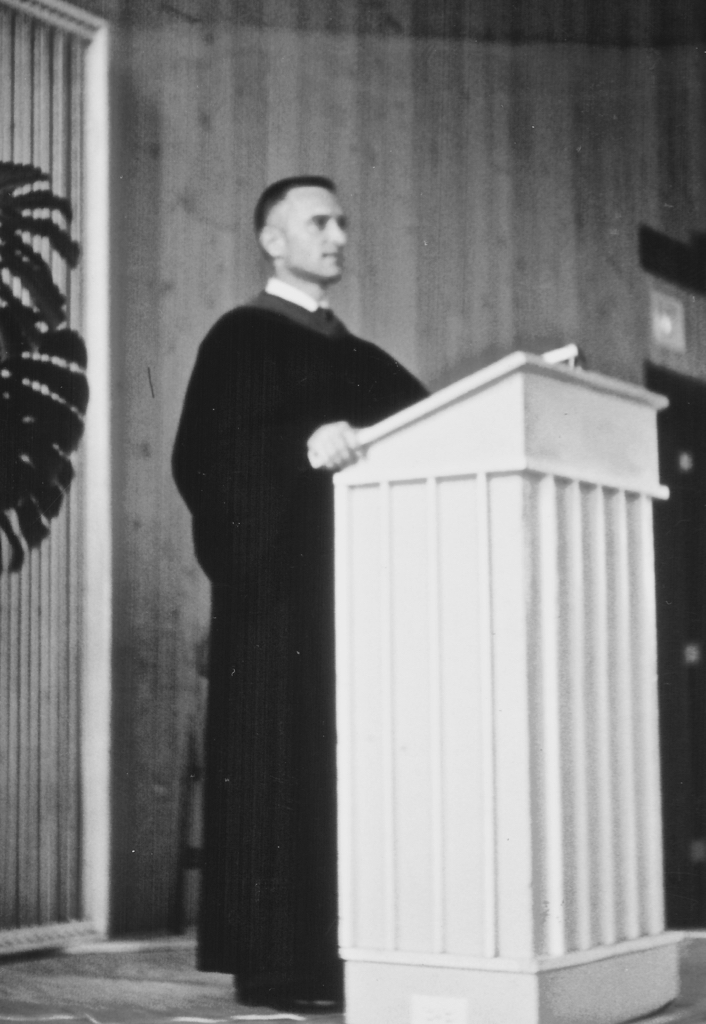

Photographs:

All photos are from the archives of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto.

Unpublished sources:

Anonymous. [Folder titled “PAUC All Church Survey 1988”].

Anonymous. “Church Timeline from February 5, 2001, Meeting.” Notes from “Visioning Our Education Ministry” meeting, 2001.

Anonymous. “History of UUCPA.” 2 pp., undated photocopy of a document (c. 200?).

Bell, Rachel. “Parish Ministers, Interim Ministers, and Intern Ministers,” timeline. 7 pp., n.d. (c. 2000).

—————. “Religious Education,” timeline. 2 pp., n.d., c. 2005.

—————. “Religious Education at UUCPA,” timeline. 16 pp., n.d. (2000).

Call, Lon Ray. Letter to Felix Danford Lion (“Dear Fe,” [sic]), 2 pp., June 11, 1949.

Collier, Ken. “Minister’s Report, 1997-1998.”

—————, and Marnie Collier. Letter to the congregation. 2 pp., July 30, 1993.

Currie, Rigdon. Untitled [letter from Currie as President of the Board of Trustees to the congregation]. 1 pg., Feb. 28, 1989.

Ruth Freeman, Cathy Leach-Phillips, Ed Milner, Ken Collier, and Til Evans. “The Dual Services Plan.” 2 pp., n.d. (c. 2000).

Hargis, Ron. “The Palo Alto Unitarian Church: An Analysis.” 2 pp., Jan., 1977.

—————, and Bill Jacobsen. Untitled memo (“We are concerned, as I know all of you are…”). 2 pp., n.d. (c. Nov., 1975).

Hamaker, Gail. “History of the Palo Alto Unitarian Church.” 3 pp., 1980.

Harrison, Bob. Untitled [memories of the Palo Alto Unitarian Church]. 2 pp., Aug. 7, 1983.

Indergand, Litsie. Untitled [letter from Indergand as President of the Board of Trustees to the congregation]. 1 pg., Oct. 17, 1989.

Jacobsen, Bill, and Diane Jacobsen. Untitled [announcement of their divorce to the congregation]. 1 pg., n.d.

Laine, Darcey. Notes from interviews conducted in 2002; and column in “The Bulletin,” the UUCPA newsletter, May 23, 2003.

Lion, Felix Danford. “Biographical data.” 1 pg., August, 1969.

—————. “Memories and Reminders” [sermon for the 25th anniversary of the building]. 5 pp., Oct. 16, 1983.

Macdonald, Charles H. (Attorney-at-Law). “Status of Loan on Parsonage of the Palo Alto Unitarian Church, 339 Kellogg Aveneue, Palo Alto, California.” 1951.

Mackay, Ned. “Rev. F. Danford Lion resigns to join church in New York.” Undated clipping from the Palo Alto Times (1972).

Niles, Alfred S. “The Early Years of the Palo Alto Unitarian Society, 1947-1950.” Typescript, 1958.

Perry, Bryce. “Staff at UUCPA.” 2 pp., Oct. 9, 1998.

Peterman, Sid. No title (“Because the interim ministry…”). 8 pp., 1973.

Schmidt, Muriel. “A Brief Resume of the Palo Alto Unitarian Church.” 4 pp., 1972.

Schwaar, Georgia. Note to Darcey Laine dated Oct. 15, 2002.

Wright, Sam, and Donna Lee. “Report from Sam and Donna.” 3 pp., April 18, 1991.