Sermon copyright (c) 2023 Dan Harper. As delivered to First Parish in Cohasset. As usual, the sermon as delivered contained substantial improvisation.

Readings

From the essay “Nature” by Ralph Waldo Emerson:

Crossing a bare common, in snow puddles, at twilight, under a clouded sky, without having in my thoughts any occurrence of special good fortune, I have enjoyed a perfect exhilaration. I am glad to the brink of fear. In the woods too, a man casts off his years, as the snake his slough, and at what period soever of life, is always a child. In the woods, is perpetual youth. Within these plantations of God, a decorum and sanctity reign, a perennial festival is dressed, and the guest sees not how he should tire of them in a thousand years. In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life, — no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes,) which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground, — my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, — all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God. The name of the nearest friend sounds then foreign and accidental: to be brothers, to be acquaintances, — master or servant, is then a trifle and a disturbance. I am the lover of uncontained and immortal beauty.

From Louisa May Alcott’s satire on Transcendentalism, “Transcendental Wild Oats”:

“Each member [of the community] is to perform the work for which experience, strength, and taste best fit him,” continued Dictator Lion. “Thus drudgery and disorder will be avoided and harmony prevail. We shall rise at dawn, begin the day by bathing, followed by music, and then a chaste repast of fruit and bread. Each one finds congenial occupation till the meridian meal; when some deep-searching conversation gives rest to the body and development to the mind. Healthful labor again engages us till the last meal, when we assemble in social communion, prolonged till sunset, when we retire to sweet repose, ready for the next day’s activity.”

“What part of the work do you incline to yourself?” asked Sister Hope, with a humorous glimmer in her keen eyes.

“I shall wait till it is made clear to me. Being in preference to doing is the great aim, and this comes to us rather by a resigned willingness than a wilful activity, which is a check to all divine growth,” responded Brother Timon.

“I thought so.” And Mrs. Lamb sighed audibly, for during the year he had spent in her family Brother Timon had so faithfully carried out his idea of “being, not doing,” that she had found his “divine growth” both an expensive and unsatisfactory process.

Sermon: “Why I’m a Mystic (But Maybe You Shouldn’t Be)”

When I was 16, the summer camp I worked for sent me to a weekend workshop led by Steve van Matre, an environmental educator. Steve van Matre was an observant educator. After several years of working with kids, he noticed that conventional environmental education, with its emphasis on teaching identification skills and intellectual concepts, didn’t wind up producing environmentalists. So he, and the other environmental educators with whom he worked, began developing activities that would — to use his words — “turn people on to Nature.”

One group of these new activities was called “solitude enhancing activities.” Van Matre felt that most of the time when we are supposedly in solitude, we are actually listening to a little internal voice that is constantly talking. Van Matre called this voice “the little reprobate in the attic of your mind,” and he said that it was a dangerous voice in some ways, because it keeps us from living in the present. (1)

When he said this, for the first time I became aware of that little voice in my own head. And that little reprobate in the attic of my mind did in fact talk on and on with no respite. Once I noticed it, I couldn’t un-notice it: it was constantly talking, on and on and on, and saying (if I were to be honest with myself) little or nothing of interest.

Van Matre outlined several activities that environmental educators could use to help quiet that “little reprobate in the attic of your mind.” I decided that I wanted to teach those activities to this children I worked with in the summer. Since I was brought up in a family of educators, I knew that if you’re going to teach something, it’s a good idea to try doing it yourself first. So I tried some of van Matre’s solitude enhancing activities.

One of these activities, which called “Seton-Watching,” was to sit outdoors somewhere and do nothing but simply be aware. Van Matre had told us about a time when he did this: He went outdoors, and settled down to stay absolutely still for some lengthy period of time, perhaps half an hour. After sitting absolutely still and in silence for perhaps a quarter of an hour, a hummingbird came along to look at his red hat band. This prompted van Matre to look up, so he could see the hummingbird. The motion of his head startled the bird and it flew away before he could see it, and he concluded he would have been better off remaining motionless, instead of listening to the little voice in his head that told him to look up.

I began trying this “Seton Watching” activity. One afternoon while sitting at the foot of a birch tree, the little reprobate in the attic of my mind finally stopped talking. In that moment, I suddenly became aware of — for want of a better way of describing it — the connectedness of the entire universe. It was quite a sensation. I then discovered that words were not adequate to describe this sensation — it was not in fact a sense of the connectedness of the universe, but something that couldn’t be put into words. Which makes sense, because this sensation only occurred when that little voice in my head stopped talking. Words are very powerful and very useful, but there are other kinds of knowing that have nothing to do with words; and trying to describe those other kinds of knowing with words must obviously be a pointless exercise.

It turns out that experiences like this are fairly common. These experiences have been classed together under the title “mystical experiences.” When the psychologist William James studied mystical experiences, he argued they had two defining features. First, said James, the person who has a mystical experience “immediately says that it defies expression, that no adequate report of its contents can be given in words.” James goes on to add: “It follows from this that its quality must be directly experienced; it cannot be imparted or transferred to others.” Second, James said, mystical states are experienced by those who have them as a kind of knowing: “They are states of insight into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect.” James also pointed out that mystical experiences tend to be short-lived and transient, and they are generally passive. (2)

Mystical experiences are fairly common — William James believed that as many as a quarter of all people have them. And that makes me wonder — what good are these experiences? I’m less interested in whether these experiences are useful, but instead I wonder whether these experiences tend to move you towards or away from truth and goodness. To use the language of the Unitarian minister and mystic Theodore Parker: the moral arc of the universe is long, and the question is whether these experiences help bend it towards justice, or not.

I think mystical experiences can lead to justice, but they can also lead to injustice. In my observation, mystical experiences, when supported by the right kind of community, can strengthen individuals to help bend the moral arc of the universe towards justice. However, I’ve also seen how mystical experiences may twist an individual towards psychopathologies like narcissism and delusion, or embolden an individual to abuse their power and indulge their greed.

Here’s what I think causes someone to follow one or the other of these two possible paths. If someone has a mystical experience and they think it makes them special and somehow better than other people, that can prove to be the path to psychopathology or abusiveness. These people tend to have mystical experiences outside of a supportive and critical community. They are hyper-individualists, and the combination of mysticism and individualism can create a toxic brew. On the other hand, if someone has a mystical experience and is part of a community that holds them accountable for their actions, then a mystical experience can help that person bend the moral arc of the universe towards justice. A mystical experience can provide a vision for a better future where Earth shall be fair and all her people one.

In the second reading this morning, the excerpt from “Transcendental Wild Oats,” Louisa May Alcott tells a story of how mysticism can be destructive. “Transcendental Wild Oats” is based on Alcott’s lived experience. When she was a girl, her father moved his family to Fruitlands, a utopian community in Harvard, Massachusetts. The men who started the Fruitlands community were mystics, and their mystical insights informed them — so they said — of how to run the perfect human community. But the Fruitlands community fell apart in seven short months. The male mystics in charge of the community were unable to grow the crops they were depending on, unable to do anything practical, while the women in the community did their best to keep the children safe and feed everyone. Louisa May Alcott’s story “Transcendental Wild Oats” is a thinly disguised satire of the Fruitlands community. Alcott lays bare the sexism and the ignorance of the men whose abuse of their mystical experiences made the lives of other people miserable.

(I should note in passing that Louisa May Alcott was a Unitarian. But hers was not an individualistic religion; hers was a religion of community, connection, and mutual support.)

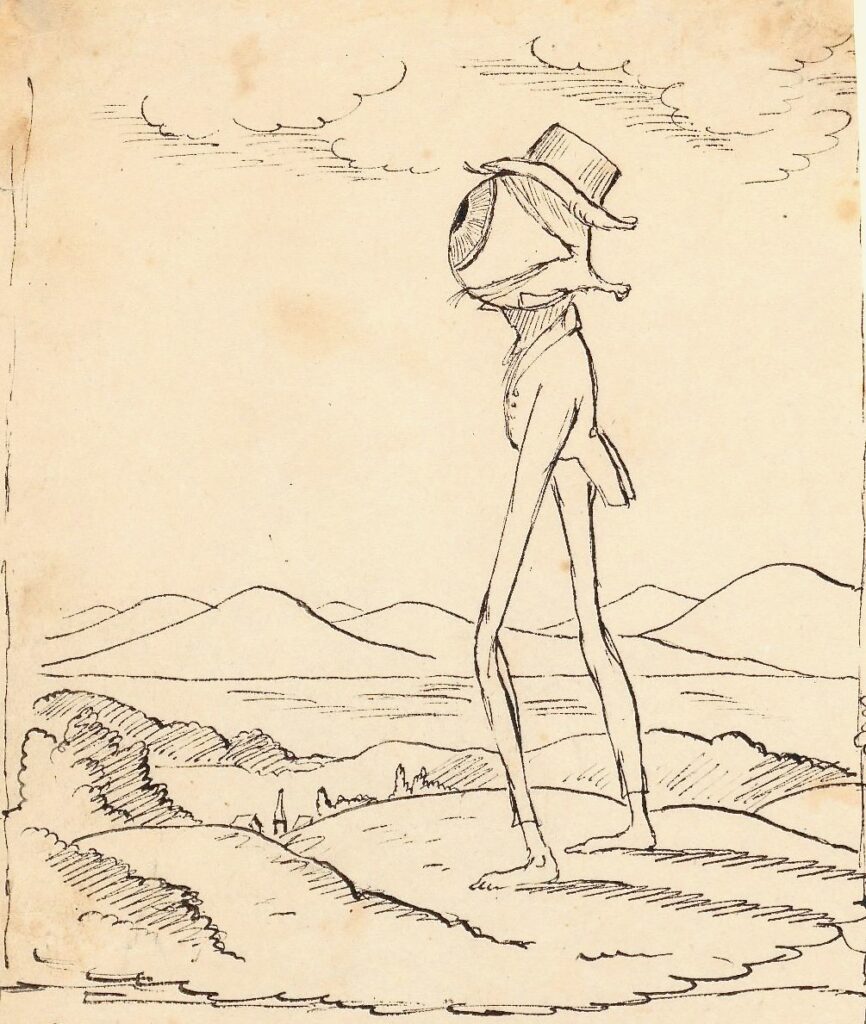

In our first reading, another Unitarian, Ralph Waldo Emerson, described one of his own mystical experiences. In a now-famous image, Emerson wrote: “…All mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.” Christopher Cranch, a contemporary of Emerson’s and a fellow Unitarian minister, drew a cartoon making fun of Emerson’s transparent eye-ball: the cartoon shows an eyeball wearing a top hat atop a tiny body with long spindly legs. (3) I think what makes Emerson’s transparent eye-ball image so prone to mockery is the fact that it’s too individualistic. This is my criticism of Emerson’s mysticism: he is too self-centered. Emerson had the opportunity to go out and wander in the fields and become a transparent eye-ball in part because he left all the housework, all the management of their children, to his wife, Lidian. (4) This sounds too much like the mysticism that Louisa May Alcott satirized. If you become a transparent eye-ball while wandering the fields in leisure, that will be quite different from the mystical experiences you might have while caring for children, or mending clothes, or cooking dinner for your family.

And this brings me to another well-known mystic, Henry David Thoreau. Thoreau was raised as a Unitarian, but left in his early twenties because the church in Concord, where he was a member, refused to offer wholehearted support to the abolition of slavery. Thoreau’s most famous descriptions of his own mystical experiences occur in this book Walden. Once again, Thoreau’s mysticism is open to mockery. Critics of Thoreau love to tell the story of how Thoreau didn’t actually lead the life of a mystical hermit at Walden Pond — he went home regularly so his mother could do his laundry and cook him dinner. It’s easy to be a mystic when your mom cooks you dinner.

But I think Thoreau’s critics miss the point. While it is true that Thoreau didn’t break out of the strict gender roles of his time, at least he did much of his own cooking and cleaning while living at Walden. And Thoreau had to go home regularly to help his father run the family business of manufacturing pencils (an appropriate role for his gender in those times). Equally important for our purposes, Thoreau also went home to attend meetings of the anti-slavery group led by his mother. The Thoreau family was part of the Underground Railroad, and Thoreau wrote that his cabin at Walden Pond served as a place to harbor fugitive slaves. And while he lived at Walden Pond, Thoreau spent that famous night in jail because he refused to pay taxes that went to support an unjust war.

We can rightly criticize Thoreau for his sexism, the unquestioned sexism of his time. And it’s easy to make fun of his mysticism. But unlike the mysticism of the organizers of Fruitlands, Thoreau’s mysticism didn’t keep him from successfully growing his own food, and building his own house. And while Emerson’s mysticism can come across as self-indulgent, Thoreau’s mysticism gave him the strength to take courageous action against slavery, and against unjust war.

When I had my own first mystical experience, I lived in Concord, where Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau had all lived. The Concord public schools gave us a heavy dose of the Concord authors, so at age sixteen I knew their stories. I had even started to read Thoreau’s Walden, and liked him the best of all the Concord authors. So when I had my own mystical experience, I had Thoreau’s example to show that mystical experiences could move one towards making the world a better place.

The justification for a mystical experience is to help bend the moral arc of the universe towards justice. This helps explain Martin Luther King’s fascination with Thoreau. I suspect King had his own mystical experiences, which he no doubt understood from within his progressive Christian worldview. King understood how his deeply-felt religious experiences could give him the strength he needed to confront injustice. Nor is he the only one whose mystical experiences helped them bend the moral arc of the universe towards justice. Hildegard de Bingen drew strength from her mysticism to enlarge the role of women within the confines of her medieval European society. Mahatma Gandhi drew on his mystical experiences to help him confront the evils of colonialism in India. And so on.

Just remember that you don’t need to be a mystic in order to help bend the moral arc of the universe towards justice. Some people have mystical experiences, and some people don’t. Having a mystical experience doesn’t make you a better person; what makes you a better person is furthering the cause of truth and justice. But if you are one of those people who happens to have a mystical experience or two, may you use it to strengthen you to help make the world a better place.

Notes

(1) Van Matre’s approach is outlined in his books Acclimatizing, a Personal and Reflective Approach to a Natural Relationship (American Camping Assoc., 1974) and Acclimatization : A Sensory and Conceptual Approach to Ecological Involvement (American Camping Assoc., 1972). The quote comes from my notes of van Matre’s workshop on 6 May 1977.

(2) William James, Varieties of Religious Experience, p. 381.

(3) Here’s Cranch’s cartoon:

(4) For an account of busy Lidian’s daily life, see the biography by her daughter, Ellen Tucker Emerson, The Life of Lidian Jackson Emerson, ed. by Delores Bird Carpenter (Boston: Twayne, 1981).