Another story for liberal religious kids. This one is from the Yoruba tradition. While this story has a mythological elements — it tells how Tortoise got the joints in its shell — it is also a morality tale. Tortoise is another animal trickster figure who is featured in many stories — sometimes he gets the better of others, but sometimes, as in this story, his greed gets the better of him. Another Yoruba story about Tortoise.

Once there was a shortage of food throughout the land. Àjàpá the Tortoise, who was a very sensible animal, was friendly with a man named Tela. Tortoise was sick with hunger, because he didn’t know where he could get food. But Tela knew where he could get food. Now and again Tela went to this place, and got food and ate it there.

At last Tortoise said to Tela, “You look well-fed, but I get nothing to eat. You are my friend, yet you never show me where you get food.”

“I thought of taking you,” said Tela, “but I know you to be very clever. I fear that you will go to my place without my permission. Because of that, I have not told you.”

Tortoise kept asking, though, and at last Tela promised to take him to the place. When they got to the place, Tortoise saw it was just a rock. But Tela sang:

“This rock must open because I, Prince Tela, the owner of the house have come!”

Then the rock opened and Tela and Tortoise went inside. They found plenty of food, and they ate until they were full. After they had finished, they left the place, each going to his own home.

The next day Tela was away from home. So Tortoise went all around the countryside, inviting all the people to come to Tela’s place to get food. When everyone arrived at the place, Tortoise sang:

“This rock must open because I, Prince Tela, the owner of the house have come!”

The rock did not know that it was not Tela who sang, but Tortoise. So the rock opened, all the animals went inside, and they finished all the food in the store.

When they had finished eating, Tortoise said, “I will be the last to go.” But just as Tortoise was leaving, the rock closed and trapped him, half in and half out.

Just then, Tela felt hungry. When he got to the rock, he saw the head of Tortoise sticking. Tela said, “How is it that I find you here? When I brought you here the day before yesterday you promised you would not come, but now you have come, and from all the footprints in the dirt it looks like you brought friends with you.”

But Tortoise was in pain, and said only, “Get me out and don’t talk.” Tela, being hungry, commenced to sing:

“This rock must open because I, Prince Tela, the owner of the house have come!”

Just as before, the rock opened. Now Tela was very hungry, and because of the food he thought lay before him, did not stop to talk with Tortoise. But when Tela went in, he saw that all was eaten, and nothing was left.

Tela was so angry that he caught Tortoise up and was about to crush him. “Have patience and I will tell you all,” said Tortoise, and he told the entire story. And Tortoise added, “I have to admit that there is something that always makes me tell things I ought not to tell.”

“I have no time for this sort of thing,” said angry, hungry Tela. He dropped Tortoise on the rock and smashed his shell all to pieces.

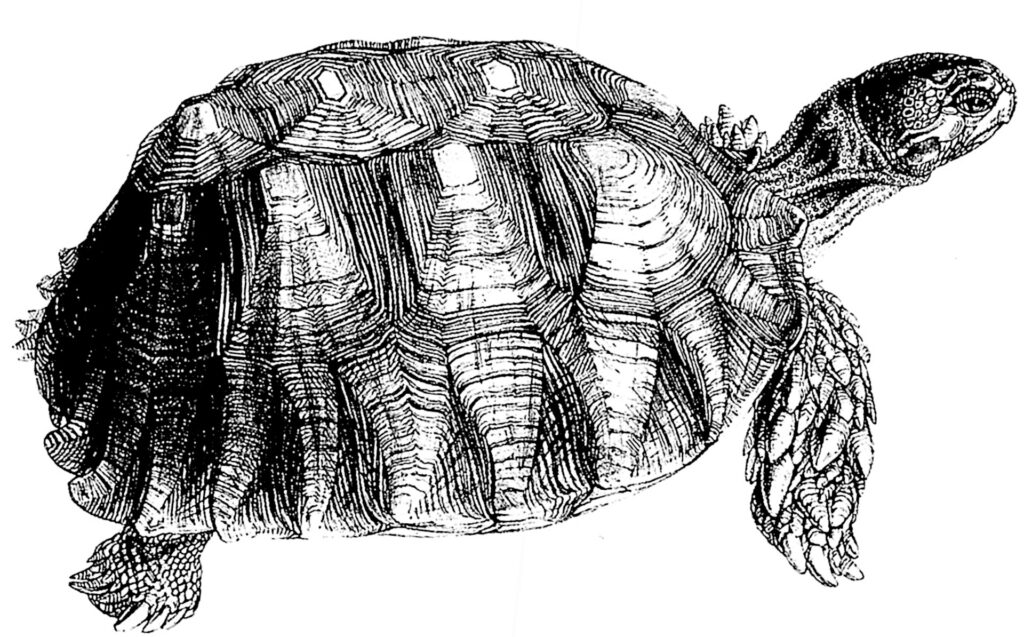

Then the big ants and other insects gathered round, and tried to put Tortoise together again. They did the best they could, but they could not mend his back properly. So it is that the joints where the insects mended the Tortoise show on his back to this day.

Source

John Parkinson, “Yoruba Folk-Lore,” African Affairs, vol. VIII, no. XXX, January 1909, pp. 180-181 doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098993

For a different version of this story, see ?gb??n ju agbára on The Yoruba blog.