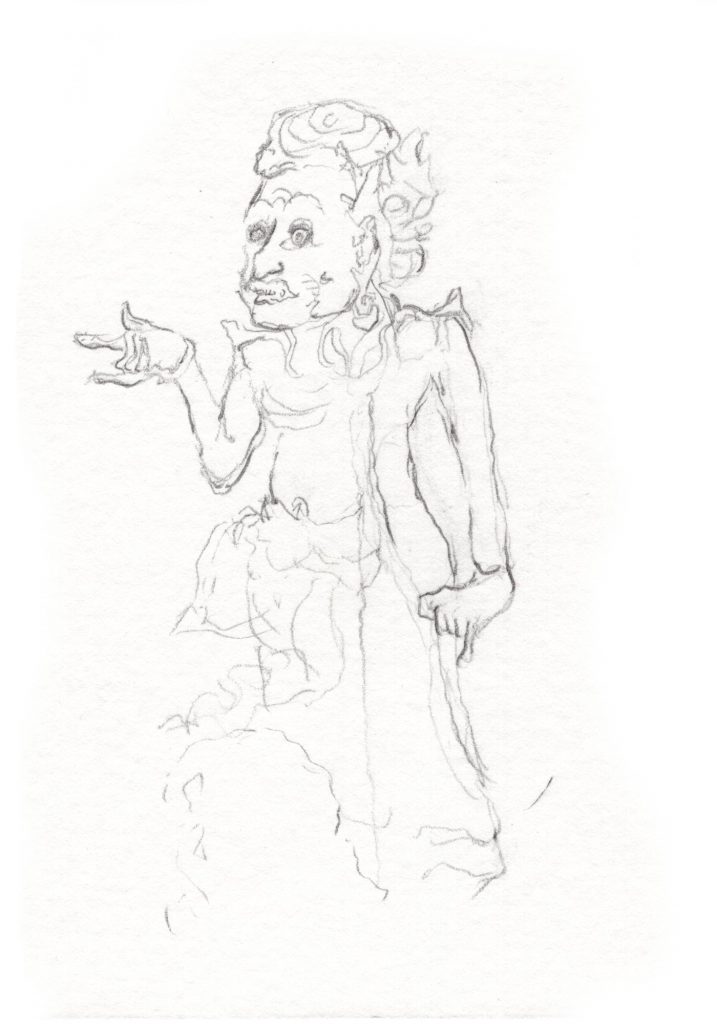

In the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, there’s a lovely small sculpture of the god Shiva with his wife Uma. It was made in the 13th century CE out of “copper alloy” in Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state in India.

But wait a minute…isn’t Shiva married to Parvati? Who is Uma?

For a partial answer to the question of Uma’s identity, I looked at the Kena-Upanishad, which can be found of the Talavakara-Upanishad. I used Max Mueller’s translation in The Upanishads Part I, Sacred Books of the East series, volume I (Oxford, U.K.: Clarendon Press, 1897), pp. 46 ff. The third and fourth khandas of this upanishad tell how Brahman, the ultimate reality or highest deity, is more powerful than anything else in the universe, more powerful even than various other gods and goddesses. Mueller’s translation of the third khanda (verses 1-12), and the first verse of the fourth khanda, reads as follows:

“Brahman obtained the victory for the Devas. The Devas became elated by the victory of Brahman, and they thought, this victory is ours only, this greatness is ours only.

“Brahman perceived this and appeared to them. But they did not know it, and said: ‘What yaksha [sprite, demon] is this?’

“They said to Agni [fire]: ‘O Gatavedas, find out what yaksha this is.’ ‘Yes,’ he said.

“He ran toward it, and Brahman said to him: ‘Who are you?’ He replied: ‘I am Agni, I am Gatavedas.’

“Brahman said: ‘What power is in you?’ Agni replied: ‘I could burn all whatever there is on earth.’

“Brahman put a straw before him, saying: ‘Burn this.’ Agni went towards it with all his might, but he could not burn it. Then he returned thence and said: ‘I could not find out what yaksha this is.’

“Then they said to Vayu [air]: ‘O Vayu, find out what sprite this is.’ ‘Yes,’ he said.

“He ran toward it, and Brahman said to him: ‘Who are you?’ Vayu replied: ‘I am Vayu, I am Matarisvan.’

“Brahman said: ‘What power is in you?’ Vayu replied: ‘I could take up all whatever there is on earth.’

“Brahman put a straw before him, saying: ‘Take it up.’ Vayu went towards it with all his might, but he could not take it up. Then he returned thence and said: ‘I could not find out what yaksha this is.’

“Then they said to Indra: ‘O Maghavan, find out what yaksha this is.’ He went towards it, but it disappeared from before him.

“Then in the same space [ether] he came towards a woman, highly adorned: it was Uma, the daughter of Himavat [the Himalayas, or snowy mountains]. He said to her: ‘Who is that yaksha?’

“She replied: ‘It is Brahman. It is through the victory of Brahman that you have thus become great.’…”

In a footnote, Mueller provides some information about Uma:

“Uma may here be taken as the wife of Siva, daughter of Himavat, better known by her earlier name, Parvati, the daughter of the mountains. Originally she was, not the daughter of the mountains or of the Himalaya, but the daughter of the cloud, just as Rudra was originally, not the lord of the mountains, girisa, but the lord of the clouds. We are, however, moving here in a secondary period of Indian thought, in which we see … the manifested powers, and particularly the knowledge and wisdom of the gods, represented by their wives. Uma means originally flax, from va, to weave, and the same word may have been an old name of wife, she who weaves (cf. duhitri, spinster, and possibly wife itself, if O. H. G. wib is connected with O. H. G. weban). It is used almost synonymously with ambika, Taitt. Ar. p. 839. If we wished to take liberties, we might translate uma haimavati by an old woman coming from the Himavat mountains; but I decline all responsibility for such an interpretation.”

David R Kinsley, in his book Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions (Berkeley: Univ. of Calif. Press, 1986), p. 36, has a somewhat different take on who Uma in this upanishad might be:

“The Kena-upanisad contains a goddess named Uma Haimavati (3:12). This is one of the most common names of the late Sati-Parvati, but this reference does not associate the goddess with Siva, nor does it associate her with mountains, except by name (haimavati meaning ‘she who belongs to Himavat,’ who is the Himalaya Mountains personified as a god). Her primary role in this text is that of a mediator who reveals the knowledge of the brahman to the gods. She appears in the text suddenly, and as suddenly disappears. It is little more than conjecture to identify her with the later goddess Sati-Parvati, although quite naturally later writers do make the identification when describing the exploits of Sati or Parvati. To devotees of the goddess, this early Upanishadic reference provides proof of her venerable history….”

How can we make sense of all this? On Hindu Blog, which gives contemporary popular accounts of Hinduism, writer Abhilash Rajendran cites the Encyclopedia of Hinduism, vol XI (India Heritage Research Foundation and Rupa Publications, 2012) p. 22, and says Uma “has thousands of names depending on which way a devotee want to perceive her.” Rajendran goes on to say that some of the key aspects of Uma’s symbolism include feminine energy, “motherly love and nurturing,” balance, harmony, and “asceticism and devotion.” She can also appear as a “fierce warrior goddess”; and in fact, Kali is one of her manifestations.

Other sources may depict Uma slightly differently, but the gist of her is always the same: the great power of the feminine. Don’t mess with Uma.