While we have to shelter in place, I thought I’d have time to turn to serious reading. There’s a pile of books on the floor next to my desk with titles like How Judaism Became a Religion: An Introduction to Modern Jewish Thought, and Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle, and Capital and Ideology.

And what have I actually been reading? Very little in the way of serious books, I can assure you. It turns out that I’m actually the teensiest bit stressed out, between the COVID-19 pandemic, and working way too many hours to get our congregation’s programs and services online, and having my usual routine completely disrupted. Without diminishing the importance of the first two, I suspect this last may have had the biggest effect on me: I thought I wasn’t much of a creature of habit, but like all humans I’m very much a creature of habit, and when my daily habits are so completely changed it’s unsettling. So I’ve been reading fluff, junk, pulp fiction — in short, guilty pleasures.

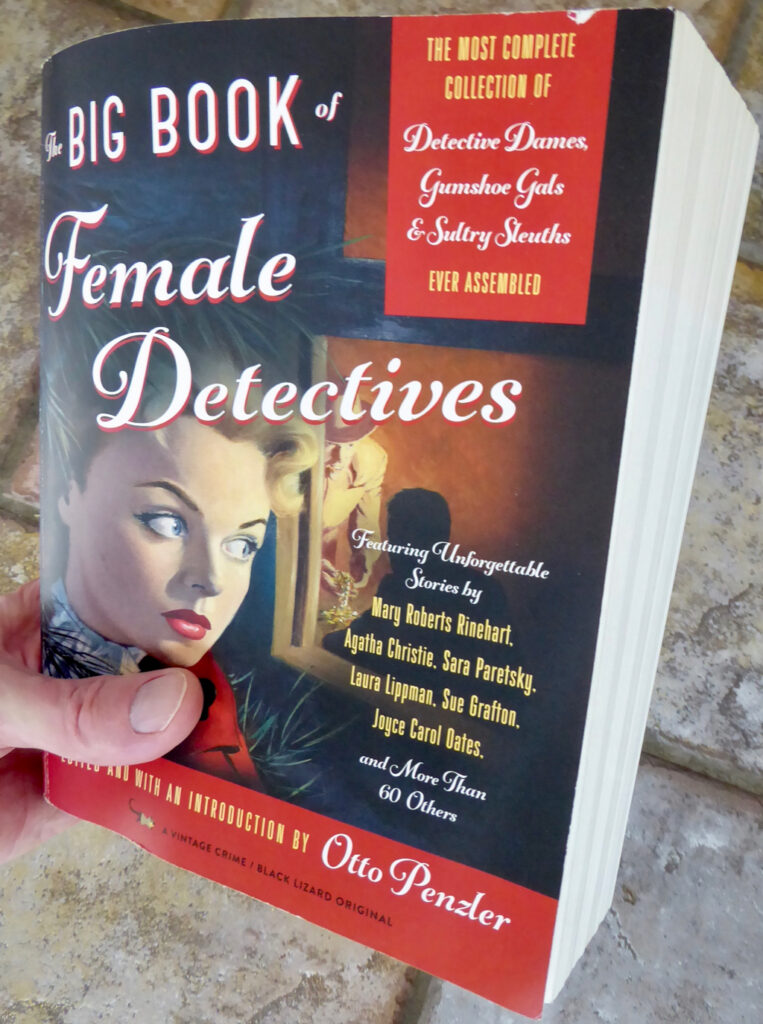

I’ve been reading The Big Book of Female Detectives, ed. Otto Penzler (Vintage Crime, 2018). It’s 1,111 pages of guilty pleasures, stories with no intellectual value at all. All right, I admit that there is one piece of serious literature in the book, a very short story (four pages) by Joyce Carol Oates, which I skipped over because every paragraph began with the word “because” and that required a little too much thought on my part. So subtract four pages, and make that 1,107 pages of pure unadulterated thoughtless fun.

The first dozen stories are British and American stories from before the First World War; many of the plots creak alarmingly under the weight of suspended disbelief. One of my favorites from this section of the book is “An Intangible Clew” by Anna Katharine Green, featuring Violet Strange, a very wealthy young woman who is secretly a brilliant detective. Here is how she arrives at the scene of the crime in this story:

“When the superb limousine of Peter Strange [Violet’s brother] stopped before the little house in Seventeenth Street, it cause a veritable sensation…. Though dressed in her plainest suit, Violet Strange looked much too fashionable and far too young and thoughtless to be observed, without emotion, entering a scene of hideous and brutal crime…. Her entrance was a coup du theatre. She had lifted her veil in crossing the sidewalk and her interesting features and general air of timidity were very fetching….”

Many of the early stories in the book — the stories are arranged in chronological order — feature female detectives who hide their brilliance under an appearance of brainlessness. Thus when you finally get to Agatha Christie’s novel The Secret Adversary, featuring Tuppence Cowley as detective, with her sidekick Tommy Beresford, you realize how innovative Christie was. Tuppence Cowley is smart, funny, and brave. She doesn’t pretend to be stupid when she’s not (indeed, it’s Tommy who isn’t very bright, and admits it), and she comes across as a real person, a three-dimensional character. The plot of The Secret Adversary whizzes along at a breakneck pace, so fast that the unbelievable parts of the plot (of which there are a great many) have gone by before you realize how unbelievable they are. And who cares about the plot anyway? — you read this book to enjoy Tuppence’s personality.

Worthy of note is a mid-twentieth century story by Mary Roberts Rinehart, once a best-selling author and now mostly forgotten. Rinehart’s “Locked Doors,” which has appeared in other anthologies, is less a mystery story than a story of suspense; but there’s a surprise ending to the story that makes perfect sense of all the outre plot elements, and while it’s not entirely believable, the ending is believable enough to make it satisfying.

The next high point in the book is a story by Sue Grafton, featuring her famous detective Kinsey Milhone. It’s easy to forget how revolutionary Sue Grafton was: not only are her stories reasonably well-written, but Kinsey Milhone is as smart, funny, and brave as is Tuppence Cowley, but Kinsey doesn’t need a man to make her complete — she doesn’t need to get married (Tuppence agrees to marry Tommy at the end of The Secret Adversary), she doesn’t need a male boss (Tuppence reports to the powerful and mysterious Mr. Carter), she’s independent and alone and likes it that way. If Kinsey Millhone is a result of the feminist revolution of the 1970s, then thank God for the feminist revolution of the 1970s.

Most of the other stories in the book have no redeeming value, but they’re so much fun to read — even if you forget them moments after you’ve finished them. These stories would make perfect beach reading, but since we’re not allowed to travel to the beach they also make perfect shelter-in-place reading, requiring no intellectual effort while keeping your mind off of current events.